Rememory & Reckoning

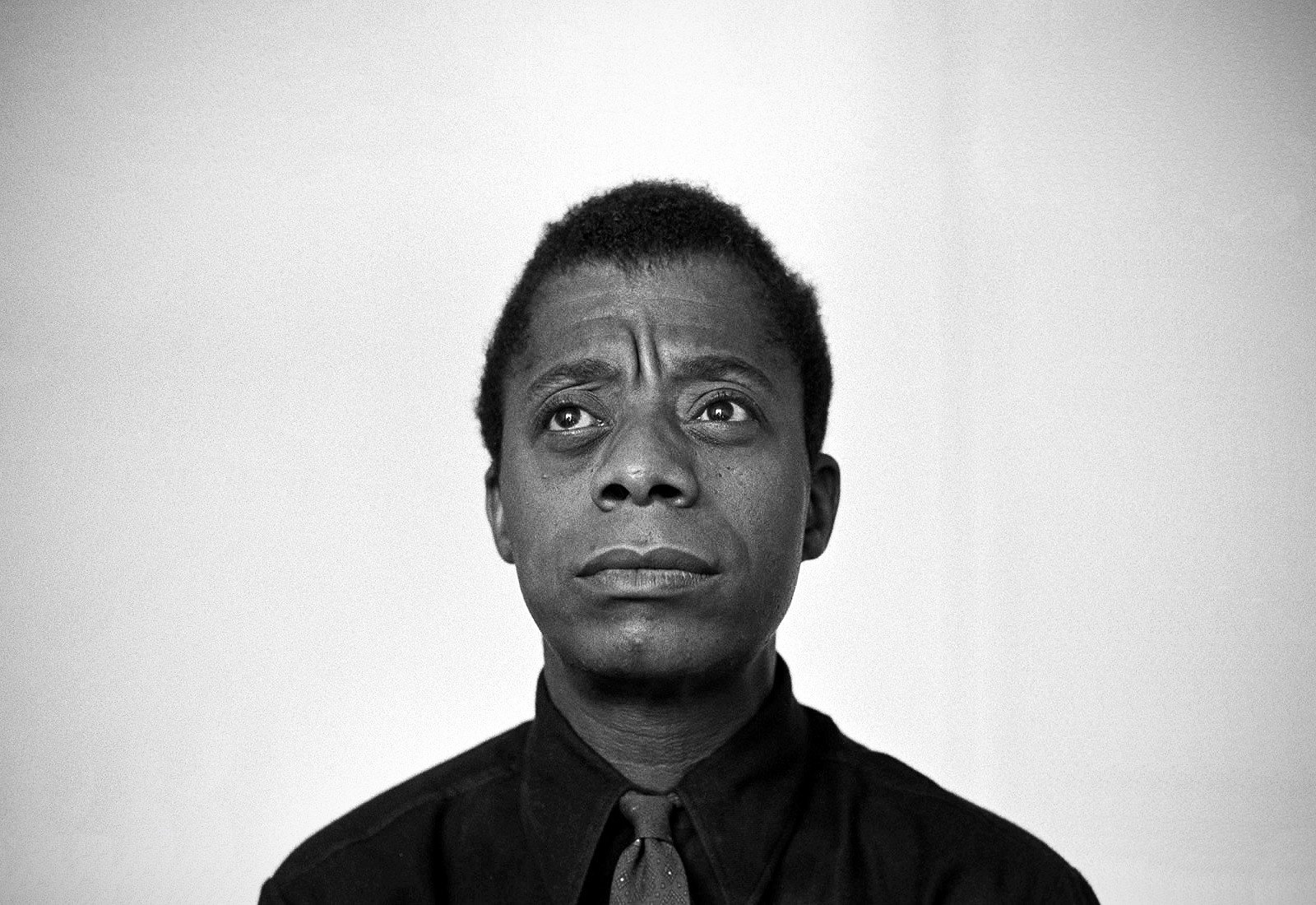

A reflection of James Baldwin then, today, and the futures that are possible.

By Mustafa Ali-Smith

There are days — this is one of them — when you wonder what your role is in this country and what your future is in it. How, precisely, are you going to reconcile yourself to your situation here and how you are going to communicate to the vast, heedless, unthinking, cruel white majority that you are here. I’m terrified at the moral apathy, the death of the heart, which is happening in my country. These people have deluded themselves for so long that they really don’t think I’m human. And I base this on their conduct, not on what they say. And this means that they have become in themselves moral monsters.

— James Baldwin, Remember This House

I would like us to do something unprecedented: to create ourselves without finding it necessary to create an enemy.

— James Baldwin, Anti-Semitism and Black Power, 1967

It is quite shocking, truly, how the words in the quotes above written by James Baldwin — one of the most notable novelists, playwrights, essayists, poets, and activists of the twentieth century — nearly 50 years ago could bear so much weight today. Words that he could not bring himself to publish before his death and remained in an unfinished manuscript titled Remember This House.

This manuscript was intended to recount the stories of some of the most prominent civil rights leaders — from their fight for racial equity to the lives of their growing sons and daughters — but the title of the unfinished manuscript perhaps foreshadowed something Baldwin was thinking about within our country.

What was Baldwin referring to when he named This House and what was it symbolic to/of?

Was it that Baldwin saw the possibility of communities — safe communities where Black people, and maybe all people, could thrive — as something happening in that present moment while also providing the country with the direction of where it should go? Was Baldwin here talking about alternative worlds and futures for Black people? Was he alluding to an elsewhere place? This House, then, emphasized remembering the ones who sacrificed in the face of an anti-Black world, but above all the sacrifice, creating a new home and house — new worlds and possibilities for them — where the prospect of a true American dream could materialize and the Black people living in it could thrive.

Remember This House would have been one of the final pieces published by Baldwin conceivably alluding to the futures possible for Black people through remembrance, and yet, throughout his life, he wrote about these very possibilities. Nearly 50 years ago, the backdrop of Baldwin’s words served as a witness of the anti-Black work he lived in, a country that had never reckoned with its own lies — its crime — which shows up in the ugliness that we see today. Today, the country is still grappling to confront the ugliness it has grown in. Those who hold some of the highest leadership roles in the country such as Vice President Kamala Harris, the first Black woman to hold that role and now the First Black Woman Democratic nominee for President, have even recently supported the proclamation that “America is not a racist country.”

What then makes America not a racist country if, on any given day, that same America discards its citizens as if they are the problem and continues subjecting them to nothingness?

. . .

Police killings, poverty, forced migration, among many others — an assertion of Black nonexistence/non-being and nothingness — are all things Baldwin wrestled with during the twentieth century though has never left this country. Baldwin recognized that those who forced terror onto Black people were in themselves “moral monsters.” However, no matter how much Baldwin doubled down on the ugliness of this country and its moral failings in confronting its crime, his writings — especially the words in Remember This House — alluded to and even explicitly stated, how Black people can “go on” in the words of Gordon Lewis by having an embodiment of a love ethic and building new futures free of simply surviving the breadth of the Negro Problem.

Baldwin’s commentary on how Black people might “go on” arose from his acknowledging that generation after generation there was — and still is — a cycle of terror among Black people, followed by death, mourning, and then finding the strength to go on and endure. It is a cycle that consists of Black people navigating a world that deep down despises their existence — an embodiment of the Negro Problem. Instead of succumbing to a life of merely surviving in this world, Baldwin turned the Negro Problem on its head, imagining and proposing how Black life might thrive beyond trying to survive or prove themselves in the face of the Negro Problem and whiteness.

This account of Baldwin’s life, then, is twofold. On one hand, it briefly emphasized rememory and the need to reckon with that history — the history of America as the colonizer, whiteness as the antithesis, and the price paid for the ticket by white America and the need to create the Negro as the problem. From there it proposes, based on Baldwin’s writings, that Black futures and worlds be — and continue to be — created in this anti-Black country. On the other hand, it is a call for whiteness to be confronted, because though Black futures and worlds can be imagined and created, the hold of whiteness in this country will persist if the lie — the crime — is never confronted and reckoned with.

Remembering

Baldwin’s writing has informed us about the possibility of Black people creating new futures and worlds — their elsewhere place — but it bears outlining why these futures are needed to begin with.

When Toni Morrison wrote her novel Beloved, she used the term “rememory” to mark an important act related to recovering and reckoning with memory with one of her main characters, Sethe. Rememoy, as Morrison might have defined it, was the act of recalling moments that had been forgotten — by choice or without knowledge of the act. They are moments of history that are made unfamiliar because they have been tucked away — discarded and unreckoned with — and at their manifestation, become a haunting endeavor based on the reality that has been made in its absence. Accounting for the history of our country is a process of rememory, a process that Baldwin was committed to.

Baldwin would argue that history is within us — that we are all walking exemplars of it. We breathe it, live it, wear it, toil with it — Baldwin himself noted that history is not something that is only read, but something that is living and in the present wake. It is seen the 2.2 million Americans locked up behind iron bars in our county’s prisons. It is the militarized borders and families pleading for freedom — the hope of that American dream. It is Sonya Massey calling the police to her home for help and shortly after being killed by them. It is, also, the bloodshed and displacement of indigenous communities by the hands of a colonized America.

What is to be made of this — this crime — and how did we get here? Why is this the anti-Black world that Black people live — and presumably, have to live — in? And lastly, what has brought the need for Black people to create new futures and worlds where they can thrive beyond it? One thing is for certain: no matter how much Baldwin’s views changed over the years of his life, one of his beliefs that remained constant was his observation and critique of the crime of America.

. . .

The crime started with one of America’s first actions — colonizing indigenous lands. These men were not innocent, and Baldwin recognized that in their actions, they tried to absolve themselves of the crime by emphasizing the Negro Problem and placing the Negro and other brown people as other. As Baldwin wrote in The White Problem:

The people who settled the country had a fatal flaw. They could recognize a man when they saw one. They knew he wasn’t . . . anything else but a man; but since they were Christian, and since they had already decided that they came here to establish a free country, the only way to justify the role this chattel was playing in one’s life was to say that he was not a man. For if he wasn’t a man, then no crime had been committed. That lie is the basis of our present trouble.

The anti-Black world as we know it originated from this crime.

They—white America—had to create the Negro and other people of color as other to not only absolve themselves from this crime, but to position themselves as the antithesis to what they declared as other so they could possess power over the land. Years later when Baldwin wrote about this very act, he argued that white people — white America — became white based on the act of the crime and the “necessity of denying Black presence, and justifying Black subjugation.” If the Black person was made evil, then white America was made good. If the Black person was made dirty, then white America was made clean. If the Black person was made unworthy, then white America was made worthy. This was not done in innocence and Baldwin grappled with the sickness that plagued the country because of it.

Similar to the words of Aimé Césaire, Baldwin believed that “no one colonizes innocently… that a nation which colonizes, that a civilization which justifies colonization — and therefore force — is already a sick civilization, a civilization which is morally diseased, which irresistibly, progressing from one consequence to another, one denial to another.” Baldwin knew the crime and the lie that covered up the crime for what it was, and accused his country of it. He wrote that “…they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it, and do not what to know it.”

The Negro Problem, then, was partially the result of what came from this—it was an invention. It was the result of placing Black people as the other. Ta-Nehisi Coates beautifully, yet woefully described the Negro Problem today in Between the World and Me when he wrote to his son, “The entire narrative of this country argues against the truth of who you are.”

This is what must be remembered: the image of the Negro was created by white America to account for its deficiencies and to position its place in society — its power. The Negro Problem was part of the lie America told its countrymen about the crime it had committed. Baldwin was conflicted by this and he believed early on that perhaps the only way for Black people to possess full being in an anti-Black world, white America would need to not only remember the original crime, but confront their refusal of it ever happening. White America would have to disband the Negro Problem and question themselves as the problem. This was the reckoning.

Remember the quotes at the beginning of this piece. Baldwin wanted white America to create themselves without having to create an enemy, and still, at the same time, he wanted Black people to recreate themselves — in their new worlds and elsewhere place as opposed to the enemy and otherness white America made them out to be.

Reckoning

James Baldwin went through his own experiences of having to grapple with his disillusion about the world. He recognized, for example, white America’s guilt and their inability to have a reckoning with their own ugliness and crimes. He knew that their inability to do this menaced the entire world, and as a result, Black people suffered.

He saw it in the ways Black communities were impoverished, the ways they were killed — murdered — without an ounce of care from white America, and he saw it in the discrimination he and others experienced.

Then, much like today, there was a crisis going on in America — a non-stop terror. Baldwin did not believe this was a hopeless endeavor though; he often argued a way out — a plea if you will for white America.

He wrote that “to survive our present crisis, to do what any individual does, is forced to do, to survive his crisis, which is to look back on his beginnings.” Baldwin continued that the dilemma of the country was that “it managed to believe the myth it [had] created about its past.” The country inevitably denied its past and needed to confront it. The crime was important to confront, but it became more important to confront how America accepted it as it was and even preached it to be a legend.

America avoided, and still avoids, the act of the crime which may be the most serious offense.

Baldwin initially believed there was no way there could be liberation based on the crime and the lies that sought to cover it up— it would continue to repeat itself unless it was dealt with. He first wrote in Another Country:

When you’re older you’ll see, I think, that we all commit our crimes. The thing is not to lie about them [the crime(s)] — to try to understand what you have done, why you have done it… That way, you can begin to forgive yourself. That’s very important. If you don’t forgive yourself you’ll never be able to forgive anybody else and you’ll go on committing the same crimes forever.

Later that same year he wrote in The Fire Next Time about the need to confront this crime and what would happen if America continued with its lie — its false history:

To accept one’s past — one’s history — is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it. An invented past can never be used; it cracks and crumbles under the pressures of life like clay in a season of drought. How can the American Negro’s past be used?

There was something that white America needed to do then.

Baldwin argued that “one has got to — the American white has got to — accept the fact that what he thinks he is, he is not. He has to give up, he has to surrender his image of himself, and apparently, this is the last thing white Americans are prepared to do.”

Baldwin was echoing what Toni Morrison would write years later in her book Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination about how white America — whiteness — would have to surrender the image it made for itself as the antithesis of Black people and deal with what was before. Morrison wanted white America to sit with what was left after they were stripped of the myths it had grown to believe. She argued that white America would have to make sense of their stripped image as “mute, meaningless, unfathomable, pointless, frozen, veiled, curtailed, dreaded, senseless, implacable.” Morrison would go on to note that this was a terror white America would face when the day of their reckoning came, a terror that would question the very life they knew and cause them to refund — or pay its dues — for the previous price they paid for the ticket. And as Baldwin would preach — what we must remember — the price America paid for the ticket was the price of becoming white.

Turning back to Baldwin’s piece On Being White… and Other Lies, he knew that one of the ways for white America to address the crisis was to commit to the paradox. If they believed that they could control and define Black people — and in fact, they did believe this because they have done it for centuries and continue to do it to this day — then they would have to divest themselves from that power to control and define themselves. However, this day seemed like it might never come, and the process would take cycles of rememory and reckoning.

Baldwin would begin to allude to an alternative for Black people: while he turned the Negro Problem on its head and gave the problem to be dealt with back to white America, his writing began to focus more on Black people defining their own freedom on their own terms. Baldwin was alluding to the need for Black people — the oppressed — to imagine and build new worlds and their elsewhere place.

Black Futures and the Need for New Worlds: The Elsewhere Place

I knew that I lived in a country in which the aspirations of Black people were limited, marked-off. Yet I felt that I had to go somewhere and do something to redeem my being alive.

—Richard Wright, Black Boy

Scholars on Black existentialism have held varying views about the trajectory of Black life and the futures that may come from it. Philosopher Calvin Warren, for example, has agreed with the realities facing America — those of an anti-Black country and its terror. Yet, Warren’s analysis of Black existentialism resides on the argument that, until there is a metaphysical transformation to the order of life, Black people will only know anti-Black terror. There is then no hope, no recourse, or the possibility of imagining these new worlds, futures, or elsewhere places for Black people.

In fact, Warren wrote that “[c]ontinuing to keep hope that freedom will occur, that one day the world will apologize for its anti[B]lack brutality and accept us with open arms, is a devastating fantasy.” What Warren was alluding to was the fate related to the life of Black people. He believed that there was nothing to strive for — that the only thing Black people could do in this anti-Black world was survive and endure the terror that could come at them.

On the other hand, Toni Morrison declared an alternative outcome for Black life. She did, much like Warren, confront us with the ugliness of this country and its crime, from its anti-Blackness to its reliance on whiteness. At the same time, however, Morrison engages us with the romanticism of an elsewhere place beyond anti-Blackness, terror, and even whiteness. She offers us a roadmap to where we, as Black and oppressed people, may imagine new futures where we thrive and find solace, here and now. Morrison did not believe that anti-Blackness and terror was the end-all-be-all fate of Black life, and instead, she imagined the possibilities of something else. But as Morrison would also note, these futures were already being imagined and created in our present moment.

. . .

Baldwin might have maintained a strong criticism of America, whiteness, and white America’s inability to reckon with its crime, and perhaps some may have even thought that Baldwin was a bit pessimistic about the future for Black people at the beginning of his writing, especially during the early 60s. However, much of Ballwin’s writings show that although he held these strong views, he remained hopeful for what was to come for Black people, especially in his later years.

When Baldwin penned The Fire Next Time in 1962, specifically in his letter to his nephew, he was grappling with the hold this country had on Black people. He wrestled with the thought of what might happen if Black people began to believe that we were the Negro white America made them out to be. Nevertheless, on the other spectrum, Baldwin was also confronting the question of in what way/s was Black liberation conceivable.

There was also some tension in Baldwin’s writing from the early 60s on what was possible with freedom and liberation. On one hand, in What Price Freedom? for example, he wrote that he — and Black people, could not be free within the social structure as it stood, but then later in the same piece he wrote that freedom was what Black people made it:

In order to be free… you have to look into yourself and know who you are, at least know who you are, and decide what you want or at least what you will not have, and will not be, and take it from there. People are as free as they wish to become.

This paradox in Baldwin’s words could be interpreted in a few ways but one question that should be considered here is how might this signal a start to Black people imagining and creating their elsewhere place? He knew that Black people were constantly subjected to terror and that white America would always view them as the problem, asking “what more does the Negro want?” So perhaps he was wanting Black people to — instead of living up to the image of what white America defined as freedom — define what freedom meant to themselves in their own way and carry this with them to their elsewhere place.

Baldwin’s thoughts on futures and worlds where Black people could thrive were also heavily informed by how he thought about love and the role this might play in those futures. See, Baldwin did not view love simply in the personal sense of showing affection to someone else or to things. He envisioned love as a state of being, or a state of grace.

The embodiment of a love ethic, borrowing the language of Bell Hooks and Cornel West, to Baldwin encompassed the universal sense of quest, daring the world, and growing in it. Baldwin’s thoughts on love in fact changed over the years according to Dagmawi Woubshet. Initially, in The Fire Next Time, Baldwin considered that white people possessed a lovelessness about themselves. He also argued that if love could be accentuated then perhaps there could be an end to the “racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world.”

Much like what Woubshet has pointed out, Baldwin began to write more about Black love and why that love was needed in Black communities beginning with If Beale Street Could Talk. It was one of Baldwin’s first pieces that exclusively focused on a Black love story. What message was Baldwin trying to send about Black love? What possibilities — futures and new worlds even — were made possible because of Black love? Baldwin, again, was redirecting his focus. He knew that the freedom he wanted Black people to redefine for themselves had to situate itself in the love that Black people had for each other if it was going to last and maintain.

Love was a factor needed to counter anti-Blackness.

There is also some speculation that Baldwin’s proposition of a love ethic to carry Black people into new possibilities and futures would in turn rub off on white America. This is inferred from the way he spoke of love. Again, when Baldwin spoke of love, it was less a feeling and more a power that would transform us — Black people — and those whom we would interact with. How would white America feel about the current worlds and futures being created by Black people in opposition to the terrors of anti-Blackness? The outcome Baldwin was hoping for was that Black people could use love as a roadmap to imagine and build their worlds and futures while at the same time signaling to white America to deal and reckon with their own terror. They would have to ask themselves why Black people found it necessary to find an elsewhere place in this anti-Black world. They would have to confront their original crime and the lie.

Creating an elsewhere place for Black people then was not just about Black people. Baldwin loved his country, and he always criticized it but maintained an element of “we” and “our” in his criticism. He could criticize America all he wanted to but, in the end, he was still a part of it, and he felt a responsibility to it. Imagining and creating new Black worlds and futures would benefit Black people in the same act, but Baldwin was hoping that this would signal to white America that they had something they needed to reckon with. Baldwin was hoping that an elsewhere place for Black people would not have one outcome but would perhaps make a ripple effect.

Baldwin taunted this idea in We Can Change the Country. He asked white America why they needed the “nigger” in the first place, but more importantly, he asked what they would do with him “now that he’s moved out of his place?” On one hand, Baldwin was underlining that Black people were already creating new worlds and futures outside of Anti-Black America — they moved out of the place of otherness America made them to be in. On the other hand, he highlighted that the outcome of Black people building these new worlds and their elsewhere place would bring about something with white America too. The idea of Black people building alternative futures and their elsewhere place was a statement against the place white America wanted the Negro to be and a declaration that Black people would not pay their dues. It was/is a declaration that Black people would not, in the words of Baldwin, be the “vehicle of, all the pain, disaster, [and] sorrow” that white America has believed they can escape. And so white America would be forced to make sense of that.

Until then, when white America would heed the message from the alternative futures Black people were making for themselves, Black people would continue to redefine what their sense of freedom was in an anti-Black world while incorporating an embodiment of love. The violence and terror would perhaps still occur — and even today we see it happening before us — but still, Black people’s elsewhere places would propel them forward. Eddie Glaude stated this seamlessly with his interpretation of Baldwin’s thoughts on the after times, his position at the crossroads, and the need to imagine a new way of being in the world alluding to new futures for America, and without a doubt for Black America:

The crossroads or the railroad junction is a way station of the blues: a place where anguish and pain are faced, where everything seems to have gone wrong, and yet a kind of resilience is found in the painful phrasing of new possibility. In the after times, hope is not yet lost, even if the call to reimagine the country has been answered with violence. So the after times also represent an opportunity for a new America — a chance to grasp a new way of being in the world — amid the darkness of the hour. But as Jimmy understood, that opportunity rests on what we do in the moment.

. . .

There has been — and continues to be — an ongoing betrayal of American Ideals where Black people have to deal with the consequences of anti-Blackness and terror, generation after generation. In the face of the Negro problem, Black people are told that the closer they can be to whiteness, the less terror they might face, but in the end, they will always be considered Black — lesser than. Baldwin always knew this was the reality of the world he lived in — a reality that consumed the country because it failed, time after time, to confront its ugliness and its original lie and crime. But Baldwin, also, did not believe that all that was to be made of Black life was for them to endure this terror and survive until death. He held on to hope. He believed that Black people could redefine their freedom during these aftertimes and imagine and create their elsewhere place — their new world.

He believed that he would no longer be the Negro that America created for their world. He placed himself out of what the anti-Black world defined him and other Black people as and sought out to create a new future — an elsewhere place — for himself and others. Given what Baldwin believed in the twentieth century juxtaposed to where we are today and the continued violence — the ongoing crisis — that is in our present, imagining and creating these new worlds and elsewhere places are how we go on. Redefining Black freedom as opposed to what has been defined for us is how we go on. A love ethic is how we go on. Violence may still be brewing in America, and most — if not all — of it is a result of America’s unwillingness to confront and reckon with its lie. But, somehow, someway, Black people are still finding a way. It is happening before us and it was happening before Baldwin. He wanted us to Remember This House — to remember the places, worlds, and futures that were being created and why they were being created. He wanted us to carry it forward.